Manga for Libraries & Schools

“Manga had a spectacular year in 2020 despite the global COVID pandemic. Readers have been diving into manga as a big form of COVID era entertainment, and there’s growth across the board, even in the channels most affected by COVID shutdowns. Now more than ever, understanding this key category is critical.”

There are a few generally accepted definitions of manga, from its literal translation of “whimsical or impromptu pictures” to the more common “Japanese comics.” There’s also the looser description many non-manga fans use, as Benn Ray, co-owner of Atomic Books, recently noted: “Most of the people looking for manga erroneously refer to it [as] ‘the anime.'”

There are a few generally accepted definitions of manga, from its literal translation of “whimsical or impromptu pictures” to the more common “Japanese comics.” There’s also the looser description many non-manga fans use, as Benn Ray, co-owner of Atomic Books, recently noted: “Most of the people looking for manga erroneously refer to it [as] ‘the anime.'”

If you’re not an avid manga reader and don’t know the difference between it and anime, or Shonen and Shoujo, understanding the ins and outs of the medium can be daunting, even if you’re familiar with Western comics’ classic superheroes and/or the many award-winning graphic novels of recent years. While you may have heard of some of the most popular manga series like Attack on Titan, Berserk, Demon Slayer, My Hero Academia, and Naruto, if you’re responsible for building a diverse, representative collection of manga, you’re going to have to expand your knowledge beyond that.

This brief primer will help librarians and educators get a better understanding of what manga is, its unique categories, and some key titles to consider for your collection and/or readers’ advisory recommendations.

Understanding Manga

Manga is a medium that covers every genre you can think of, for readers of all ages and interests. The most popular manga are initially published in Japan where cultural differences can make finding “age-appropriate” titles more challenging, so understanding manga’s specific categories, and how “Amerimanga” may differ, is a critical first step to building a strong collection.

The two most popular categories primarily serve middle grade and young adult readers.

- Shōnen refers to titles intended for tween and teenage boys. Many other subjects and genres can be covered in a Shōnen title, but the focus of these titles typically is on action and/or humorous plots featuring male protagonists. Shōnen also includes the popular “Mecha” and “Harem” sub-genres.

- Shōujo refers to titles intended for tween and teenage girls. Many other subjects and genres can be covered in a Shōujo title, but the focus of these titles typically is on relationships and emotional interactions, typically featuring female protagonists. Shōujo also includes the popular “Magical Girl” sub-genre.

The most popular Shōnen examples include Attack on Titan, Naruto, and One Piece, while Stan Sakai’s Usagi Yojimbo is a classic in the category. The most popular Shōujo examples include Boys Over Flowers, Fruits Basket, and Glass Mask. Avatar: The Last Airbender and The Legend of Korra are excellent Shōnen-adjacent recommendations which have found a growing audience thanks to Nickelodeon’s anime series debuting on Netflix during the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, while Disney has put a Shōujo spin on some of their most famous characters in series like Descendants, Fairies, and Kilala Princess.

- Kodomomuke translates as “intended for children” and indicates manga for children younger than the typical Shōnen and Shōujo audience, generally 3-to-10-years-old. They are usually more gender-neutral than traditional Shōnen and Shōujo manga.

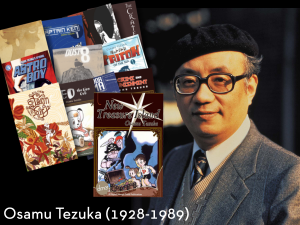

The most popular Kodomomuke examples include Doraemon, Dragonball, and Pokemon, as well as Tezuka’s classic Astro Boy. Perhaps not surprisingly, this is another category where Disney has found success with manga adaptations of several of its popular characters, including Stitch.

Because manga isn’t “just for kids” in Japan, there are distinct categories for older readers and more mature interests, too.

- Seinen refers to titles intended for adult men, 18 or older. Like Shōnen, it covers a variety of subjects and genres, but with a stronger focus on realism and sophisticated storytelling.

The most popular Seinen examples include Berserk, Crayon Shinchan, Golgo 13, and Oishinbo. Kazuo Koike & Goseki Kojima’s Lone Wolf and Cub and Hiroaki Samura’s Blade of the Immortal are also considered hugely influential classics in the category.

- Josei refers to titles intended for adult women, 18 or older. Like Shōujo, it covers a variety of subjects and genres, but with a stronger focus on mature, realistic, and at times, troubling relationships.

The most popular Josei examples include Chihayafuru, Nodame Cantabile, and Usagi Drop. Bizenghast is a notable example of a series that fits the category despite originally being published first in the United States, in English, sometimes referred to as “Amerimanga” and making it manga-adjacent for some readers.

- Yaoi/Yuri is a term for manga which typically features mature (and occasionally graphic) romantic relationships between two male (Yaoi) or two female (Yuri) protagonists. These titles are traditionally created by women for women, though certainly not exclusively.

The most popular Yaoi and Yuri examples include Killing Stalking, No Touching at All, Ten Count, and Citrus, Murciélago, My Lesbian Experience With Loneliness, respectively.

And finally, there’s a broad range of non-traditional and manga-adjacent titles to be aware of including but not limited to “Amerimanga.”

- Doujinshi typically refers to self-published manga titles from creators who originate from all over the world, or titles with a manga influence that don’t neatly fall into traditional manga categories. Some contain fan art that is a parody or derivative of traditional manga, sometimes with content very far removed from the source material.

“For fans, by fans,” Doujinshi can be a controversial category for manga purists. Some of the most popular examples include Boundry of Emptiness, The Full Room, and The Tyrant Falls in Love, while a more liberal definition might also include the majority of manga-adjacent and -inspired titles from publishers as varied as Antarctic Press and Tokyopop.

Building a Diverse Manga Collection

Want to dive in even further?

Our in-house manga fanatic, Rob Randle, teamed up with our in-house librarian, Moni Barrette, to explain manga’s unique categories and recommend key titles available in Comics Plus for every age and interest. Check out our curated collections spotlighting recommendations for readers looking for traditional manga originally published in Japan, or a wide variety of Manga-inspired readalikes from Western creators.

Also, our panel of experienced educators and librarians—Mike Barltrop, Jillian Ehlers, Michael Gianfrancesco, Ashley R. Hawkins, Kat Kan—shared their insights on everything you need to know about manga in this free webinar. After viewing, you can download your Certificate of Completion.

Circulate All The Manga!

“This is probably the strongest manga subscription service available in English outside of Shonen Jump and Crunchyroll.” School Library Journal

In our Resource Center, you’ll find a range of marketing materials and other resources to help take advantage of the resurgent interest in Manga and drive circulation in your library.

You should also engage your readers to find out what they’re already reading AND watching on their own. Beyond our resources, familiarize yourself with other great manga resources, including Good Comics for Kids, Manga Bookshelf, Manga Librarian, and No Flying No Tights.

And when balancing your budget between physical and digital collections, take advantage of Comics Plus’ unlimited simultaneous access to expand and diversify your manga collection—without breaking your budget!